IBON International Foundation Inc. works with social movements and civil society constituencies to build consensus on development issues and bring these to global attention. It has special consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council. Based in Metro Manila, Philippines and works through regional hubs in Kenya and Senegal. It operates a representative office in Brussels, Belgium.

The need for a people-centred, rights‑based framework

The dominant economic model is characterised by unbridled corporate resource extraction and production, a historical reliance on emission-heavy fossil fuels, and wastage. People’s rights have been eroded in this paradigm of monopolistic capitalism.

This includes the rights of indigenous peoples to their ancestral domains that are under siege from state and corporate land-grabbing practices. With neoliberal norms of trade and investment, deregulation and privatisation influencing many governments, production and consumption patterns remain heavily entangled with corporate power and the dominance of foreign capital and elites in the countries of the Global South.

People-powered sustainable consumption and production

To shift from unsustainable patterns of consumption and production that pollute and destroy ecosystems and violate people’s rights requires addressing systemic issues including trade and investment rules, economic structures and national development policies. Moving towards systemic sustainability requires looking at the relationships of governments, corporations, civil society and people’s organisations, and how exploitative relations could change.

Sustainable consumption and production is about a lot more than resource-efficient economic growth, it must also be about the defence, assertion, upholding and realisation of people’s rights.

People-powered sustainable consumption and production encompasses government’s accountability to the people, including adhering to their mandate to hold corporations accountable. It also includes a focus on people sovereignty that promotes self-sufficiency from the local through to the national level, including support for the innovative community practices that support sustainability. Our work with communities in Kenya and the Philippines provides valuable lessons regarding the need to assert people’s rights and of the primacy of people’s power and initiatives.

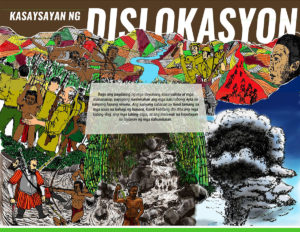

Case study: The Aeta‑Hunguey of

Capas, Tarlac, Philippines1

The indigenous Aeta-Hunguey people in Capas, Tarlac are fighting the construction of the 9,450-hectare New Clark City, which has been promoted as a grand showcase of ‘sustainable’ and ‘environmentally friendly’ urban living.

This project, initiated by the Bases Conversion and Development Authority in 2013, is masterminded by the Asian Development Bank and state actors from Japan and Singapore. This so-called ‘sustainable’ city project has already displaced farmers and Aeta communities in the Tarlac and Pampanga provinces.

The project has vested interests, including the Armed Forces of the Philippines that is entitled to a portion of project revenue in commercial development of these reservation areas. The principle of ‘Free, prior and informed consent’ was not followed; military presence in and control of the area serves to intimidate and repress residents in their opposition to the project. Intensive excavations have deforested mountains and rerouted river systems to make way for highways.

Construction has destroyed ecosystems and pushed entire communities off their land, resulting in them losing access to their banana plantations and fruit-bearing trees.

The loss of access to natural resources and introduction of the wage system is destroying the Aeta communal way of life.

The Aeta and small-scale farmers have not taken the theft of their rights lying down. They have undertaken mass protests, set up barricades and entered dialogues with relevant government units. Farmers are using broadcast seeding to quickly cover large swathes of land that has been bulldozed and grow new palay (rice) saplings.

This guerrilla farming strategy is a form of political assertion. Resistance to the project continued in 2020 despite the very difficult living conditions brought about by a repressive government response to COVID-19.

The community asserted their rights through bungkalan – collective land reclamation and cultivation by farmers in situations of agrarian dispute. This enabled the community to feed itself in a time when people had lost their jobs and could not afford basic food staples.

The steadfast resistance to encroachment on the Aeta’s way of life has inspired others to join their cause to help them fight eviction, hunger and government neglect and repression.

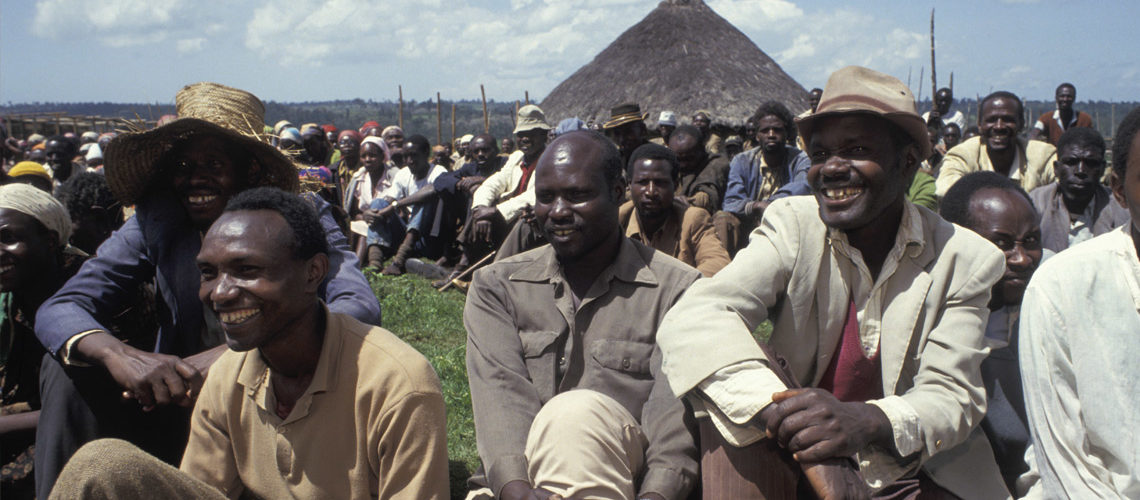

Case study: The Ogiek of the Mau Forest, Kenya

Since colonial times, there have been numerous attempts to evict the Ogiek living in the Mau Forest in western Kenya. The Ogiek describe this heritage of pain and torture as kanyalilet.

A community member notes that while Kenya gained its independence from colonialism, the Ogiek never got theirs. The Mau Forest has been under government ownership for decades and it has deteriorated significantly. Trees are cut down to make way for plantations, large-scale farming, logging and human settlements.

The Ogiek have been systematically evicted and removed to the fringes of the forest. Their traditional way of life is at risk of extinction. They long for the days when they were stewards of the Mau Forest, which was then whole and alive.

“Now, where is the medicine from the forest? Where are the bees? Even those wild animals, where are they now?”

Kiplang’at, community elder, Mau Forest, Kenya

While deprived of their ancestral domains, the Ogiek have adapted by engaging in other forms of livelihoods, while still working to defend the forest.

They took up farming and livestock production while still maintaining traditional practices of beekeeping and honey production and applied indigenous knowledge to manage their natural resources. Beekeeping is integral to the Ogiek livelihood and way of life, as honey is used in traditional ceremonies, as medicine, food and a source of income.

The Ogiek have won a legal battle to be recognised as indigenous peoples in the African Court of Justice and in Kenya’s High Court. And they continue to actively advocate for their rights to their ancestral domain now and for the future generations of the Ogiek peoples.

Protecting rights is not enough

In both communities, the elements of people-powered consumption and production are in place. The assertion of people’s rights is illustrated in their valiant struggles for access to their ancestral domains, and for food sovereignty. Both attempted to hold governments and corporations accountable and promoted self-sufficiency, community action and the development of innovative practices.

Their experiences highlight the link between sustainability and the promotion of community and people’s rights. Their ability to shape their own reality, however, is threatened by systemic barriers, such as land ownership models, corporate dominance and state-sponsored violence and militarisation.

There needs to be drastic systemic changes to support ongoing people’s initiatives towards people-powered sustainable consumption and production.

- IBON International. 2020. ‘Rights for Sustainability: Community-led practices on people-powered consumption and production.’ [Online] Available: iboninternational.org/download/rights-for-sustainability-community-led-practices-on-people-powered-consumption-and-production/.